This interview is with Dr Fritz Schellander, for CANCERactive and was originally published in Issue 4 2006 icon

Please note that Dr Schellander has now retired.

Interview by Ginny Fraser

What’s Love got to do with it?

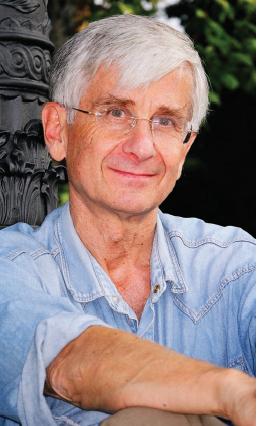

Dr Fritz Schellander operates the Liongate Clinic in Tunbridge Wells. A Doctor who tries to help people with the best of Orthodox and Alternative therapies, he has an extremely objective and measured approach to the treatment of cancer. He is particularly interested in the areas of diet and stress, including adrenaline therapy. He admits to being genuinely moved by the plight of cancer patients and gave up his orthodox practice because he wanted to commit more time to those who were ill. We sent Ginny Fraser along to interview him.

When something interests you, I always think that it reflects some aspect of yourself. I have great empathy with the suffering and struggle that cancer patients have when they are suddenly thrust into a situation where their life is threatened. There is something about that whole constellation of human experience that I have been moved by and drawn to. Apart from the human aspect of it, cancer is also a huge intellectual and academic challenge.

When something interests you, I always think that it reflects some aspect of yourself. I have great empathy with the suffering and struggle that cancer patients have when they are suddenly thrust into a situation where their life is threatened. There is something about that whole constellation of human experience that I have been moved by and drawn to. Apart from the human aspect of it, cancer is also a huge intellectual and academic challenge.

Thus says Dr Fritz Schellander one of the few doctors who are straddling the apparent divide between orthodox and complementary oncology. It is a comment typical of this thoughtful, kind man, who has been treating cancer patients in Tunbridge Wells since 1997 with a very interesting approach based on a working model relating to adrenaline described in detail later in this article.

Anyone who has developed an aversion to the sight and smell of hospitals would be refreshed by a visit to Dr. Schellander’s practice The Liongate Clinic. It is set in a quiet and leafy residential street in a beautiful light-filled Victorian house with huge windows and a warm, friendly atmosphere.

He originally qualified as a medical doctor in Vienna in 1965, then trained as a dermatologist doing research. This work brought him to London in 1971. After he re-qualified in the UK he eventually realised that he was more interested in people than in pure research and decided to retrain as GP. He worked in that field in Sussex for fourteen years.

I wanted to do my own thing

I wanted to do my own thing  I became increasingly frustrated toward the end of my years in general practice because of the restrictions of being a GP. I had a very large list of nearly 3000 patients (current average list size is 1650) and there was never enough time to give patients the attention they needed. I felt my freedom was curtailed - I couldn’t always do what I wanted to do because I was bound more and more by bureaucracy. I wanted to do my own thing and express my growing interests, I suppose, he said.

I became increasingly frustrated toward the end of my years in general practice because of the restrictions of being a GP. I had a very large list of nearly 3000 patients (current average list size is 1650) and there was never enough time to give patients the attention they needed. I felt my freedom was curtailed - I couldn’t always do what I wanted to do because I was bound more and more by bureaucracy. I wanted to do my own thing and express my growing interests, I suppose, he said.

Chelation Therapy and more

In 1989 he began working privately in Tunbridge Wells, initially using nutritional therapy. But then he introduced his ’unique’ programme incorporating chelation therapy and an increased awareness of stress and lifestyle factors, which he applied successfully to patients with primarily cardio-vascular conditions. During the next seven years or so he saw occasional cancer patients and gradually began to be drawn towards this type of work.

The only way I can put it is that the plight of the cancer patient moved me, he says. They have a very rough deal and I wanted to help ease their burden, where possible.

He visited a number of established alternative cancer clinics from Mexico to Germany and eventually formally added a cancer-related treatment programme that, in fact, was already running along quite comfortably. Some good early successes with cancer patients ensued and from 1997 Dr. Schellander began to attract increasing numbers of patients with cancer.

His work is rooted in orthodox science throughout. I do not knock or belittle orthodox medicine, Perhaps, one day we will realise that we got it very wrong,

Perhaps, one day we will realise that we got it very wrong, which has made great strides in many areas, but there is no system that isn’t capable of improvement and there is no room for complacency in oncology, he commented. In oncology we have the problem that progress has been very, very slow and we are still living with the paradox of treating cancers with carcinogenic agents! This feels completely wrong to me! Perhaps, one day we will realise that we got it very wrong, although one has to admit that in a very small percentage of cancers chemotherapy has excellent short- or medium-term results.

which has made great strides in many areas, but there is no system that isn’t capable of improvement and there is no room for complacency in oncology, he commented. In oncology we have the problem that progress has been very, very slow and we are still living with the paradox of treating cancers with carcinogenic agents! This feels completely wrong to me! Perhaps, one day we will realise that we got it very wrong, although one has to admit that in a very small percentage of cancers chemotherapy has excellent short- or medium-term results.

Listening to the complex

The crux of Fritz’s approach to cancer is his awareness of its complexity. What occupies me very much is the multiplicity and extraordinary complexity of factors that contribute to our well-being. Just making a diagnosis of cancer is not enough. We need to know not just what this patient has got but make an extended diagnosis: Why does this patient have this problem now?

Sometimes you get an answer and sometimes not but this should not stop you enquiring.

An initial consultation will take one and a half to two hours, and what I learned in general practice helps a lot in terms of learning from what the patients actually say. Often people often unconsciously refer to what is wrong with them in phrases like I can’t stomach this, or I’ve taken it to heart or It’s something that’s hard to swallow. Sometimes this is strikingly reflected in their illness. The English language is rich in expression, which may well have a sound biological basis.

I am interested in every aspect of my patients’ lives. If you are really interested, people will often divulge things they have never said before. I simply listen to all of it and gradually a picture will form like an albeit incomplete jigsaw. There is a huge complexity in human beings and if you don’t consider this to the best of your ability then you are taking too mechanical an approach. A lot of oncology can be like that. Alternative approaches can be equally prescriptive, but what is always called for is a greater understanding of the human being in front of you and their circumstances.

Environment, diet and stresses

Much of today’s organic food is still deprived of essential nutrients

Much of today’s organic food is still deprived of essential nutrients Amongst the factors that Dr. Schellander will consider in exploring the complexities of each patient are environmental toxins they may have been subject to - like oestrogens, heavy metals, magnetic fields, pollutants. Often we can only guess what our systems have to deal with. Even if you eat a really good diet all your life, you are still breathing air that is polluted. Much of today’s organic food is still deprived of essential nutrients. We will never be able to know every factor. Our environment is now permeated with thousands of chemicals, which may be harmful in even minute concentrations over a long time.

Amongst the factors that Dr. Schellander will consider in exploring the complexities of each patient are environmental toxins they may have been subject to - like oestrogens, heavy metals, magnetic fields, pollutants. Often we can only guess what our systems have to deal with. Even if you eat a really good diet all your life, you are still breathing air that is polluted. Much of today’s organic food is still deprived of essential nutrients. We will never be able to know every factor. Our environment is now permeated with thousands of chemicals, which may be harmful in even minute concentrations over a long time.

Psychological traumas or conflicts, by contrast, are often easier to identify, and can act like booster injections that may link back to previous painful experiences. Patients with cancer often have a recent history of losses, major conflicts, and often longstanding stresses with resultant fatigue from childhood and a prolonged time of stress all kinds of stresses, from earlier in life, from their own disposition, even. More research is building up in the scientific literature, which points to possible pre-natal damaging influences, such as alcohol, heavy metals, etc.

My impression (which official statistics bear out) is that the younger generation now is more vulnerable than previous generations. Cancers in young people are going up, breast, ovarian and prostate cancers (all, incidentally, hormone related cancers), which used to be diseases of much older people are being seen at much younger ages. The pattern of cancers has changed and onset is becoming much earlier. It appears as if peoples’ resistance is eroded at an earlier stage, perhaps by the toxicity in the world and by the stresses around them.

Speaking with a quiet passion for the subject, he said, The thing with complexity is that it is hard to work with. Some practitioners might deal with it by increasing the complexity of their own approach adding more and more remedies and supplementation for example. In orthodox medicine the complexity is not often acknowledged the simplicity of saying That’s a cancer, here’s some chemotherapy - it may extend your life is what fits best into a system where not enough time is available for patients who find themselves suddenly in a life-threatening crisis.

We close our eyes and we don’t ask the questions because we don’t have the answers. We have limited time, a limited budget, a limited approach. That’s the best we can do. As a result patients are being offered solutions that actually are not always very effective and potentially very damaging.

Every now and again there are new drugs introduced. There is a great stir but actually it only adds a matter of weeks or months to life expectancy. Until recently there hasn’t been a single study that could conclusively show that radiotherapy to the breast has any effect on survival and yet we apply it almost routinely to often very young patients. Many patients would not choose chemotherapy and radiotherapy if they knew the real facts, the real scientific evidence. A study has been reported which claims that nearly 70% of oncologists would not opt for chemotherapy, if their turn came.

What we offer here at this Clinic are treatments based on SOME clinical and research evidence, though not enough to satisfy some of my colleagues. However, it is always safe and generally affordable. These criteria are important, especially for patients for whom no proven or non-toxic treatments can any longer be offered elsewhere. We also pride ourselves in a high continuity of care and easy availability.

What we offer here at this Clinic are treatments based on SOME clinical and research evidence, though not enough to satisfy some of my colleagues. However, it is always safe and generally affordable. These criteria are important, especially for patients for whom no proven or non-toxic treatments can any longer be offered elsewhere. We also pride ourselves in a high continuity of care and easy availability.

Treating patients at all stages

Patients come to Dr. Schellander at three stages. The first have had a diagnosis but have a fear of orthodox medicine or have been put off it in some way. He claims these people can be quite difficult to deal with because they could actually be helped quite effectively by orthodox medicine, such as surgery.

The second category has embraced conventional treatments such as chemotherapy and wants to combine it with other treatments in the hope that that will get better results. Hyperthermia (heating) is one of the treatments on offer at the Liongate clinic, which has been proven to be able to significantly enhance the results from chemo-and/or radiotherapy. (See Ginny Fraser’s article in icon issue 3, 2005.)

The third category of patients with cancer that Dr. Schellander sees comprises those who, in his words, have tried everything and have been given up on by conventional medicine, having been told there is nothing else that can be done for you.

They come in desperation, having had their hopes shattered. We see people who have had all hope  They come in desperation, having had their hopes shattered

They come in desperation, having had their hopes shattered taken away and that is tragic. It is not a question of giving people false hope - hope is not a rational thing. It is cruel to take all hope away. After all, there is no life without hope.

taken away and that is tragic. It is not a question of giving people false hope - hope is not a rational thing. It is cruel to take all hope away. After all, there is no life without hope.

Once such patients have been through the proven treatments and they have not worked, then it would not appear unreasonable to try approaches that are not considered proven so long as they cause no further discomfort or damage. Naturally, these patients are very hard to turn around because they are already toxic from their previous treatments and often present at a very late stage. Many patients no longer look for a cure but are hoping for a life extension and an improved quality of life. It is not uncommon to see patients who have come with a prognosis of six months to live and are still alive and well two or three years later. Sadly, all such patients’ evidence remains anecdotal and is never entered into any research data so nobody really knows how many patients have been treated successfully this way and what it may have been that ultimately helped them.

Adrenaline in cancer therapy

Dr. Schellander feels that it is hugely beneficial for anyone who is concerned with cancers to develop a working hypothesis and some of his work is based on the work of Dr. Fryda, who first focused upon the possible importance of a chronic lack (yes, lack) of adrenaline.

Most of us with a smattering of knowledge about cancer would immediately think adrenaline = one of the bad guys. We call it the stress hormone and the conventional wisdom is that it can even be a cause of cancer.

But apparently it is not so simple.

Dr. Fryda’s work states that a chronic LACK of adrenaline is a very important factor in causing cancer. This view is based on accepted physiological and endocrinological knowledge, and led her to develop a complex, but logical treatment schedule which can be applied to practically everyone with cancer, either alone or in conjunction with orthodox therapies.

Says Dr. Schellander, Adrenaline has had a very bad press. But there is no life without adrenaline! No life without cortisol, another major stress hormone. Adrenaline is a prime mover in all our bodily  Adrenaline has had a very bad press

Adrenaline has had a very bad press functions and is required for every adaptive reaction, whatever the stressor. Without adrenaline you cannot have good sex, run for your life, achieve, fight back, fight any infection or stand up in public. You cannot be depressed in the presence of sufficient adrenaline.

functions and is required for every adaptive reaction, whatever the stressor. Without adrenaline you cannot have good sex, run for your life, achieve, fight back, fight any infection or stand up in public. You cannot be depressed in the presence of sufficient adrenaline.

Interestingly, depression is not an infrequent precursor in the history of patients with cancer.

Stress is best redefined as anything and everything that forces you to make an adaptive manoeuvre. Stress is adaptive energy, which is good. However, if you have too much adaptation e.g. shift work or long flights; if life is difficult; if you are agoraphobic; if you are diabetic; then the demands on the adrenaline supply are higher. Some people run out at 30, 50, 80. We all have a finite supply.

But stress in itself is not necessarily a bad thing. For example, if you have a conflict or a row you can feel absolutely drained, yet if you subject yourself to the stresses of climbing a mountain you can feel elated. As long as stress is followed by stress recovery it is OK. If it’s conflict after conflict after conflict, that is when it becomes debilitating. Patients will often know exactly what I mean when we discuss this.

The hypothesis moots that everyone is subject to intermittent or chronic stressors (physical, environmental, psychological) from the day we are born (and some say even before then). The body is then forced into an adaptive response and adrenaline is the most important hormone in this process.

After many years of stresses, the adrenaline system gets pushed into exhaustion and three key functions begin to suffer. First is storage of sugar in the cells. Insulin removes sugar from the blood and deposits it as stored energy in the cells. Adrenaline is a natural opponent of insulin and mobilises stored sugars should the need for more energy arise. When this doesn’t happen, because the adrenaline is in short supply, there is an accumulation of storage sugar in cells. This problem is  Adrenaline is a natural opponent of insulin

Adrenaline is a natural opponent of insulin  further increased by the relative increase of nor-adrenaline, a cousin of adrenaline, which leads to vaso-constriction, thus leading to decreased blood flow and oxygen supplies. These mechanisms threaten the very survival of such cells, which in order to survive must get rid of sugars and create energy at the same time. The solution is to revert to a more primitive, plant-like process of sugar fermentation. The end result of this is lactic acid, which in turn is known as a mitosis (cell division) stimulant and thus encourages cellular proliferation. This could be a possible mechanism of early tumour development.

further increased by the relative increase of nor-adrenaline, a cousin of adrenaline, which leads to vaso-constriction, thus leading to decreased blood flow and oxygen supplies. These mechanisms threaten the very survival of such cells, which in order to survive must get rid of sugars and create energy at the same time. The solution is to revert to a more primitive, plant-like process of sugar fermentation. The end result of this is lactic acid, which in turn is known as a mitosis (cell division) stimulant and thus encourages cellular proliferation. This could be a possible mechanism of early tumour development.

Stress in itself does not cause cancer, but prolonged stress can limit your ability to produce adrenaline, continued Schellander. Many people I see say that they have been tired for years through continued and prolonged stresses, like a difficult marriage, problems with children, money and so on. People say that they have been pushing themselves for years. They need a coffee or a cigarette or some sugar just to get going. For some this could have been going on since infancy with bottle feeding.

This is a view with which patients can readily identify. But what does it mean for the patient in terms of the treatment regimes Dr. Schellander prescribes?

The ’all-round’ approach

The regime would be highly individual, but would include strict dietary guidelines, regulation of sugar metabolism, correction of over-acidity, detoxification and supplementation, increasing the oxygen supply to the cells and further measures to improve the adrenaline-producing glands.

The key aspects of a treatment programme are to encourage regenerating healthy adrenaline function rather than stimulating the system further. There is too much talk about immune stimulation. Patients are often depleted and over-stimulated and do not need yet further stimulation. Compare the cellular defence with an army. It the troops are inspired by a good general they will do a good job, but they cannot keep going on the front line indefinitely, especially if the food and supply lines are down.

Using Dr. Fryda’s hypothesis, you can consider looking at many treatment approaches and ask the question, Is this adrenaline sparing or adrenaline enhancing? Good nutrition would be enhancing. Prayer or meditation might be adrenaline sparing. We would aim to raise the level in the adrenaline banks by stopping wasting it and finding ways to enhance it.

When you define complementary oncology what do we really mean? Orthodox oncology surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy - is almost entirely concerned with eradicating the tumour, but with less regard for the patient.

Complementary oncology, too, is very much aware of the need to employ tumour-inhibiting interventions, such as hyperthermia, and would not shun an early operation or radiation therapy to temporarily stop or slow down the growth of a brain tumour.

However, complementary oncology adds an acute awareness of the patient’s general well-being, his environment, past, individuality and more. This will put some power back into the hands of patients, who are otherwise completely helpless in the face of an unknown enemy. complementary oncology adds an acute awareness of the patient’s general well-being

complementary oncology adds an acute awareness of the patient’s general well-being

At the end of it all I want to see someone standing up with strength and full of confidence, he concludes.

It’s an encouraging statement to hear from a cancer doctor and probably an image most cancer patients might dream of for themselves. Dr. Schellander’s emotional encouragement is evident, but so too is the science and intellectual rigour of his approach, which combine to make him a very balanced choice for anyone wishing to go beyond conventional approaches to cancer treatment.

Dr Schellander has now retired.